Founder FAQs: Did I always want to be a founder?

This post is a first step towards greater sharing and transparency about my experience as a founder.

While in San Francisco for GitHub Universe (and Next.js Conf, the DevGuild AI Summit, and a friend’s beautiful wedding), I found myself needing to be deliberate in choosing what side-events to attend. This description made the GitHub-hosted Women in Tech dinner immediately a “yes” RSVP:

Share your voice and wisdom with a group of powerhouse women committed to advancing technology - and our place in it. It will be a unique opportunity to engage in meaningful conversations, exchange insights, and build valuable connections in a relaxed and bespoke setting.

Over a beautiful dinner at Dalida, Sara Dean facilitated a set of radically candid conversations around our experiences as senior technology leaders – and as women. One of the takeaways was to commit to an action item inspired by the evening.

As one of the only founders in the room, I was asked a lot of questions about my experience and committed to trying to be more transparent in sharing what I’ve learned. While I hope my perspective is useful to many founders regardless of their backgrounds, I would love to see – and inspire – more female founders.

Even beyond this dinner, I’m frequently asked questions such as:

Did I always want to be a founder?

How did I become a founder?

How did I meet my cofounder?

How did we decide on CodeYam?

What is the founder work “life” like?

…etc.

Answering everything in one go would be book-worthy, or at least book-length. In the rest of this post, I focus on the question of “Did I always want to be a founder?”. My goal is to describe my non-linear journey, and highlight some of the skills I learned and unlearned in becoming the software startup founder I am today.

Did I always want to be a founder?

Short answer: “no”.

As a kid, “what I wanted to be when I grow up” constantly shifted: from ice cream truck driver to an astronaut to a marine biologist to a lawyer. Becoming a software startup founder never crossed my mind.

It’s not for lack of exposure to business ownership; my mom actually is a serial entrepreneur. She founded a series of businesses during my childhood, ranging from petsitting (pre-Rover, she cornered our local market) to sports (she currently still runs the Fencing Sports Academy in Fairfax City, VA).

It’s also not for lack of exposure to science and technology; my dad has a PhD in Systems Engineering, worked at an Aerospace and Satellite Communications company, and now teaches Math and Computer Science. My younger brother learned game development and took apart / built a computer when we were kids.

Despite missing the early signals, in hindsight, my early passions are a natural fit for being a software startup founder. I was (and still am!) relentlessly curious and devoured books and drove my mom crazy with “why” questions. I loved creatively solving challenging and complex problems, spending hours inventing and then solving crazy math equations. I loved creating, often inventing games and fantastical stories for my classmates. And most of all, I loved helping people. Rather than growing out of these childhood passions, I feel like I had to learn to grow into them. This took years.

Relearning How to Learn: Recalibrating Risk Perception and Fear of Failure

As a freshman at Harvard, I initially chose classes in unfamiliar subjects based on interest. Many of my peers took the same classes for an easy A, which made for a punishing grade-curve. So, I adapted to an incremental approach choosing courses I felt confident I could succeed in, sometimes with significant effort. While this led to better grades, my choices were constrained to subjects that felt doable. I only began to choose more challenging courses again once graduation became more certain.

After college, unlearning this incremental approach took years. I had to overcome my fear of failure and a misdiagnosis of its inherent risks. Today, failure indicates that I’ve attempted something hard and meaningful. It’s an opportunity to learn. By failing to tackle something extremely difficult, I end up making greater progress and learning more than through a series of incremental successes. The risk is not in trying and failing; it’s in not trying at all.

While there are still perfectionist tendencies and moments where the fear – and pain – of failure resurfaces, I can separate out the emotions from the reality. It helps that I’m still a deeply curious person. I often reframe failure as a chance to learn through fun, or at least interesting, challenges and problem-solving.

Chasing My Curiosity to San Francisco: Startups, Pivots, and Hyper-Growth

Shortly after my college graduation, while working as a paralegal (full-time) and fencing coach (part-time), I felt an urge to explore. So, I pursued opportunities to fuel this curiosity through extracurricular classes, side projects, and volunteer work. I took an innovation in business class at Harvard’s Extension School and volunteered my time to support an EdTech startup.

Around this time, I noticed that mobile technology and software applications, especially social media, were exploding in usage. I’d been early-ish to Facebook (no surprise given where it originated) but now there was this app-explosion. I felt that technology was going to radically change our lives over the coming years, for better or worse (I hoped for better).

My career north star has been having the biggest positive impact I can on people at scale. I was drawn to software and technology and an urge to learn about this field and, if possible, have a positive impact. I wanted to be in the heart of this software application wave – and so I moved to San Francisco.

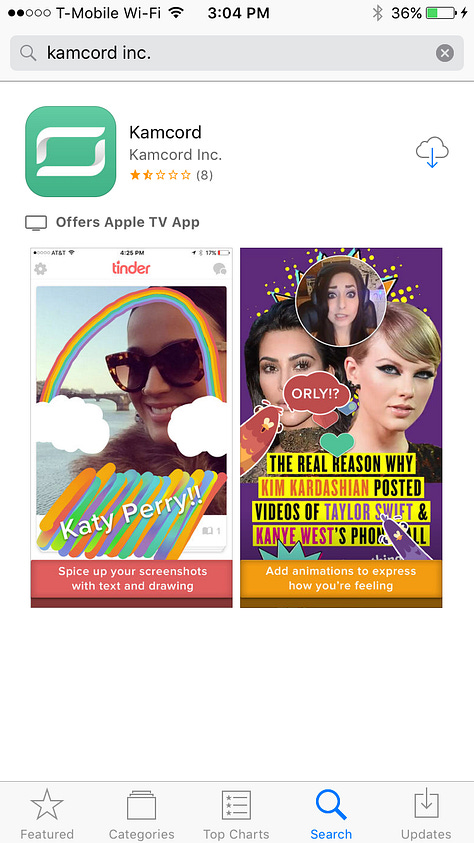

At the urging of a college friend, I joined the team at an early stage startup called Kamcord which was very early to mobile screen recording. When I joined, the team was working on an SDK (software development kit) for mobile game developers that allowed them to easily integrate screen-recording functionality for their players, along with a social community and video-sharing platform for mobile gamers.

A few months later, Apple announced a product called ReplayKit that offered the same functionality in a more native way. The Kamcord founders decided to pivot to mobile game live streaming, which quickly found product-market fit and took off.

Our streaming platform grew rapidly to millions of monthly active users (MAU) and some of the biggest streams had hundreds of thousands of concurrent viewers. Even more exciting, we launched virtual goods that enabled streamers to monetize their fanbase and make a living; this was far before the “creator economy” was as robust or known as it is today and was an incredibly meaningful product to our dedicated users.

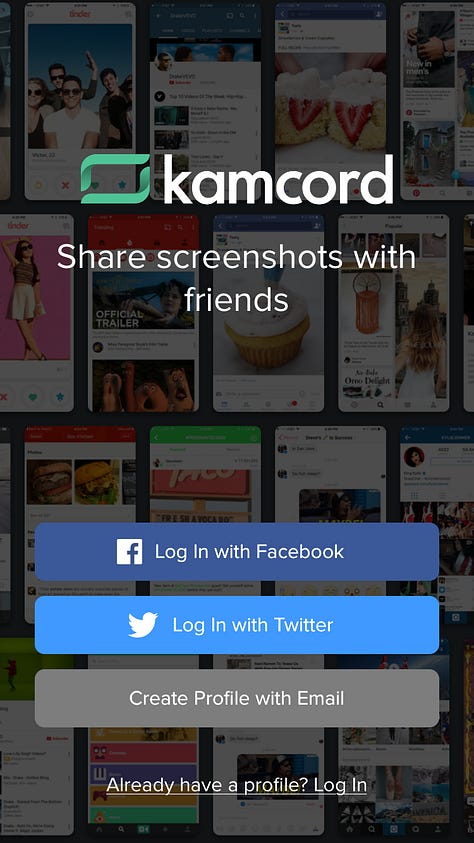

However, we struggled to gain similar traction in other non-gaming content verticals (we’d tried to expand to beauty live steaming, for instance) and our growth slowed. We pivoted again to a new idea: to a mobile social app based on sharing reactions via short videos (think Loom screen-recording meets Snapchat mobile social experience). While we could get users to try this app, retention was terrible — we had a “leaky bucket” situation that no amount of user acquisition could repair.

When we failed to improve retention, we scrapped this app. In hindsight, it was likely a great feature (similar to Instagram stories) but not sufficient to achieve traction as a stand-alone application. We then explored a series of other ideas before ultimately being acqui-hired (acquired for the team) by Lyft.

I deeply admired the three Kamcord founders; I had the joy of continuing to work with two of them, along with some of my old teammates, at Lyft during hyper-growth post-Kamcord acquisition. The founders and the team they had built were incredibly special, and I feel lucky to know and have worked with them all.

To me, the Kamcord founders embodied what I thought founders should be: brilliant, charismatic MIT graduates who incubated their startup at YC and combined serious product and engineering skills. While I loved working with and for them, for a long time I didn’t self-identify as someone who could become a founder because I didn’t relate to the archetype I’d invented.

In a surprising twist, it was during Kamcord’s final and most challenging pivot and the struggle of going from nothing to an idea that I unintentionally first started to think and act like a founder. During this time, the Kamcord founders gave our team high autonomy. In my attempt to help our team navigate the idea maze and build something meaningful, I learned the skills and leaned into the traits that, I realize now, make me an effective founder.

I, oddly, thrived in the highly ambiguous and challenging scenario of knowing what we had done failed but not having a clear “what’s next”. I encouraged the team to experiment, ultimately getting the founders’ and team’s buy-in to try out the GV design sprint process. This helped us generate and validate (or invalidate) a series of new ideas, with three of them reaching the prototype stage.

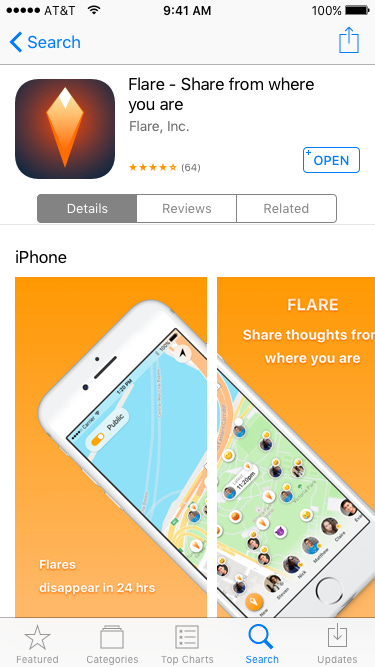

Our ideation process explored many different problems and opportunities. We came up with hundreds (my best guess!) of ideas, from bitcoin applications to smart speakers and voice recognition to ML/AI facial recognition to location-based social to a skincare community to group-based messaging platforms. To this day, I still think some of the pain points we wanted to tackle and product ideas we had were quite exciting!

During this time, I also discovered that building products, ideally with a few close collaborators, is something I deeply enjoy – and am good at (better with practice). I love the blend of customer and market discovery and finding a problem and opportunity, then figuring out how to solve it through software. While I wasn’t a manager at Kamcord (only becoming one later while at Lyft), I learned how to collaborate with and, on occasion, lead an extremely strong team that included a mix of generalists and specialists across product, marketing, design, and data science.

At Lyft, I learned into developing my product and go-to-market skills focusing on new technology products, from launching a redesigned rider app to being a founding member of Lyft’s Bikes & Scooters team. Working on zero-to-one products and then growing them to dozens of cities, thousands of riders, and millions of rides was an incredible learning experience. There was also the added adventure of being at Lyft during hyper-growth and immediately pre and post-IPO, which is a unique chapter in any company’s lifespan. I gained invaluable experience building, launching and scaling new products and managing a team. However, only at the tail end of my time at Lyft, did I consider that I might want to “one day” become a founder.

What’s Next

Since this post is already quite long, I’ll aim to write a separate post about how and why I ended up becoming a founder when I did.

Spoiler: this was in large part thanks to South Park Commons team, as well as with the encouragement from mentors, friends, and former colleagues including Adi Rathnam, who was one of Kamcord’s co-founders, and an incredible product leader at Lyft and beyond.

If you enjoyed this post or found it useful (or not), please let me know. Your questions, suggestions, and comments will help me shape the future of this personal blog.

Special thank you to Dani Raskovsky and Pär Winzell for your feedback on an earlier draft.